A fairly recent self-help title admonishes all to “don’t sweat the small stuff.” I’ve often imagined the author of this advice working in a correctional library. My edge-you-muh-cated guess is that after a few years dealing with the sociopathic personality, his book might’ve had a very different title and focus, more along the lines of, say, Hunter Thompson’s summation of Sonny Barger’s crew at the end of his Hell’s Angels: “Exterminate all the brutes!”

Rules abound in the correctional library. There are library (internal) rules, and prison (external) rules. Often the external rules of the prison compel the Librarian to make a new library rule–or at least modifications of an existing rule.

One of these prison rules is a concept called “accountability.” For obvious reasons, the administration must know at all times where each inmate is. To fulfill this mandate, it is incumbent on the inmate at all times be where he says he will be. When the inmate fails to reach his stated destination, he is said to be ‘out of place,’ and he is in a world of trouble.

A few months ago while working a late shift in the law library, I was at the photocopy counter reviewing inmate legal copy requests. It was a little after 6PM, which marks the 1st evening movement. A law library ‘regular,’ a Mr. Joseph Shmoe, came in, wished me good evening, and took a copy request form from me. Since we average 15 requests per shift, I continued reviewing requests.

Several minutes later, I came to the place on the counter where Joe Shmoe left his legal copy request. Upon reviewing his request, I had some questions about a few papers. I called Mr. Shmoe to the counter. No response. I called again, a little more insistently. Still no response. I then asked the men in the room if anyone had been designated the drop-ff person for Mr. Shmoe’s copy work. It looked like 15 deer in the headlights.

Now, Mr. Shmoe has a problem. He’s no longer in the library, which is where he should be. The rule of the building is that if you come in at 6PM, you must stay until the next scheduled movement, unless you are called out on legitimate prison business. So Mr. Shmoe is now ‘out of place.” It falls to me to notify the officer’s station that this inmate is no longer accountable at the law library, his stated destination before leaving his housing unit.

But a funny thing happens on the way to the officer’s station — a Twilight Zone moment, if you’ll indulge me. Because between the copy counter and the officer’s station, I step into a criminal justice alternate universe, where the known laws of corrections as I’ve come to know them no longer apply.

To wit: I reach the officer’s station, and there is a lieutenant whom I’ve known for years talking with a relatively new sergeant who’s still learning the ropes of the place. I tell my story. The Lieutenant listens. He then recommends that I call the inmate back up to the library and ask him about his disappearance. Now, it’s here that library responsibility and security concerns begin to clash, and I point this out by saying, “Since he left the building, doesn’t that fall to you?” When these words leave my lips, they are seized by some apparently bored-but-enthusiastic wind sprite, who gives each one a fierce twist, and coats them with holier-than-Thou attitude before hurling them into the ear canal of my colleague, who apparently receives the message, “Do I have to tell you how to do your job?”

We all can agree that there are much better ways to start your evening.

The officer balks. “I’ve got more important things to do than chase down an inmate for his copies. This is petty.”

The Librarian balks. “Since when is inmate accountability ‘petty’? He left the building, which he’s not permitted to do.”

“Who says that? Inmates can come up here and leave. They just have to do it before the end of movement.”

Now I am convinced that I am a marionette and Rod Serling’s hiding somewhere up in that drop-ceiling manipulating and giggling away. “Then there’s no consistency here. Because the other officers who run this place at night run it that way.”

“The guy is not out of place. Do what you gotta do. I’ve got other things to take care of.”

When I left the library three minutes ago, I was a confident Librarian, sure of myself and of my duty. I now turn and walk back to my post, dazed and confused…

…and this ain’t the first time. Consistency in applying the rules is a problem that corrections seems powerless to solve. I suppose all workplaces suffer from this to a greater or lesser extent.

At the second movement an hour-and-a-half later, Mr. Joseph Shmoe returns for his legal copies. I interview Mr. Shmoe, who tells me that he entrusted his copy work to a man we’ll call ‘Freddy.’ Well, “Freddy,’ he no speaks the English so good. Mystery solved.

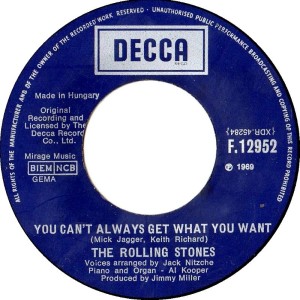

You’re only as good as the information you have. In prison, that’s doubly important. And you don’t always have the information you need in prison.

¡Ay, caramba!