When you hear of prisoners working in law libraries trying to get out of jail, does that rankle you?

When you hear of prisoners overturning their convictions on a ‘technicality,’ does that anger you?

When you hear of prisoners costing your state millions of dollars in court costs, does that confuse you?

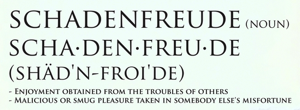

Many people react with negative emotion when they hear of such things. Many people think it absurd that prisoners retain certain rights even after incarceration. Many people think it’s a crime that prisoners have free access to the courts when law-abiding citizens have to pay hefty attorney fees and court costs. Many people find it disgusting that inmates manipulate the law after they have broken it. Many people hear about ‘cold scrambled eggs’ civil suits filed by disgruntled inmates and wonder why the system allows this abuse in the first place.

Here’s the thing —

When contemplating the rights of the incarcerated, don’t think of the folks in jail. Rather — think of yourself.

If you were unconstitutionally detained, illegally searched, wrongfully accused, or unjustly convicted, what would happen? Would anyone care? Could you help yourself? Would you be able to get the attention of the system who wronged you? Would you be able to regain your freedom? Would you be able to clear your good name?

The American system of criminal justice says:

“As citizens, we all of us have post-conviction remedies that can correct these egregious mistakes.”

“Citizens will retain the right of unimpeded access to the courts.”

“Citizens may be represented by state-appointed counsel.”

“Post-conviction remedies exist that citizens may take advantage of, including ineffective assistance of our trial counsel.”

“Citizens may submit civil suits describing a problem with conditions of confinement.”

“And we will make this access free, so that all who find themselves ill-used by the justice system may have their day in court to obtain justice.”

Law libraries and the concept of access to the courts do not exist to give the idle and the cunning a way of cluttering up the court system or a way of manipulating the law to their own sordid ends. They exist for you and for me, the free, law-abiding citizen. Why? Because the criminal justice system is imperfect and occasionally unjust. Without these remedies and procedures, you’d rot in jail, or stay there until they let you go.

For most of us, it’s difficult — if not impossible — to imagine how you could be going about your business in the world, and then suddenly become mixed up in a tragedy of circumstances that ultimately leads to your imprisonment. But you must understand that this scenario happens. And it happens more often than we realize. What if it happened to you? I know if I was on the wrong end of the law, I’d want legal remedies and procedures in place that gave me the chance to regain my freedom.

Thankfully for us, we have such a system. The wrongfully accused and unjustly convicted have the right of unimpeded access to the state and federal courts for appealing problems pertaining to their criminal convictions,. and for filing civil suits addressing some problem pertaining to their incarcerated lives.

Folks who don’t have this enlightenment of why the justice system works as it does are prone to say with exasperation, “Only in America!”

Ad thank God, or your lucky stars, that this is true. Because America gives you the chance to get out of jail, clear your name, and come home again.

The court vigilantly screens all submissions, and when it discovers a charlatan, it uses language like “Without merit,” “Failure to state a claim,” “Malicious,” “Harassing,” “Frivolous,” or “Abusive of the judicial system.” The courts know the games some inmates try to play. Do not, therefore, think of the jailhouse manipulator of the law who just wants to get out of jail — he’s the one who gives the post-conviction system the bad reputation that it has. His ilk and their machinations are the price we pay for post-conviction remedies.

Rather, think of a loved one, and the remedies they would need in order to convince the system that they were wronged and must be let go.

Prison law libraries are not about law-breakers. They’re about us — the law-abiding citizens who occasionally find ourselves on the wrong side of the prison walls.