When it comes to jailhouse humor, you either get it, or you don’t.

I get it. The fact that I get it makes me a warped individual. But please consider the truth of this next statement of self-evaluation — I was warped before I ever set foot in any prison. I truly believe that there’s a certain personality type that is drawn to corrections. It’s folks like me. I yam what I yam an’ that’s all that I yam.

Today, two amusing things were said that were too funny to forget, so — as is my regular habit — I took time to write them down.

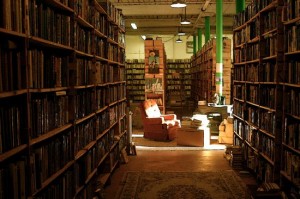

The first happened at the circulation counter in the lending library. We’ve been doing our annual inventory here all this past week, and one of my circulation clerks was assigned to the computer to check circulation records when a shelf list card is found but not the corresponding book.

My cataloger — one of the Library’s more enthusiastic ball-busters — comes over to me holding a Complete Idiot’s Guide text in his hand. Gesturing to it, he says: “Maybe you can ask them to write one on prison libraries so you can find out what you’re supposed to be doin’.'” Then he quickly backs away, tittering like a school-girl.

I appealed to my inmate clerk manning the circulation computer. When I think of this man, the phrase ‘tiny mountain’ comes quickest to mind. At 6’1″ and nearly 300 power-lifting pounds, he sports a ‘Mr. Clean’ bald head that looks like it’s been staved directly into the center of his massive torso because he has no neck. This clerk also suffers from PSTD as a result of extensive combat experience. He has been trained to kill, knows many ways to kill, has seen many people killed, and has killed many times. And we in the library all know this.

I say: “Do you like me?”

In response, the clerk purses his lips to me suggestively, and wiggles his eyebrows in a most inappropriate manner (well, he’s been in a long time).

I say “Good.” Gesturing toward Mr. Ball-Buster, I say “You think he needs to be slapped?”

The circulation looks at his fellow clerk, then at me, returns his attention to his computer monitor and, as he resumes typing, says: “A pound of linguiça and I’ll do him any way you want.”

If the response you just finished reading struck you half as funny as it did me, then right now you are piddling in your pantaloons. Because I swear on a stack of flapjacks that I laughed for a full 30 seconds. The reason? You’re not supposed to encourage violence in the prison. Prisoners aren’t supposed to solicit goods for services rendered. And — usually — prisoners aren’t as up-front about their feelings toward each other. All these taboos taken together makes the clerk’s response not just funny but hilarious.

*

A little while later, I’m standing in our book-binding work area. There are four inmate clerks with me, including the book binder. One of my clerks — a heart disease patient for decades and who’s suffered several heart attacks in the last three years — is telling me about his recent chest pain, which compelled the prison to send him to an outside hospital. He says:

“They tested me, they found nothing wrong, and said ‘Don’t worry about it.'”

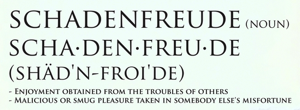

Another clerk (a friend of his for the past 40 years) says with concern in his voice, “Well, then, you must have angina.”

The heart patient replies “No. I’ve never had angina.”

At this, another clerk — in his Puerto Ricaῆo accent — quietly says to the book binder, with a wink: “He says he never had vagina?”

*

Jailhouse humor. You either get it, or you don’t.